The drone industry aspires to a future of high-frequency operations in low-altitude airspace shared by multiple operators. Today in Singapore drone operator Skyports Drone Services relies on an informal daily sharing of flight plans for strategic deconfliction with other operators. However, the company recognizes the need for a more automated system to support a scalable commercial ecosystem.

“Well-programmed systems make fewer mistakes than humans,” says the head of technology from Skyports, Jef Geudens. “Commercial success will require each pilot to monitor ten or twenty aircraft, effectively becoming an airspace manager.

“We can only reach that scale with a fully automated system for deconfliction. Neither are narrowly segregated operations likely to prove viable.

“If drones only operate in narrow corridors, we may as well use delivery vans,” says Geudens. “Commercial operations require wider areas of airspace controlled by automated systems.”

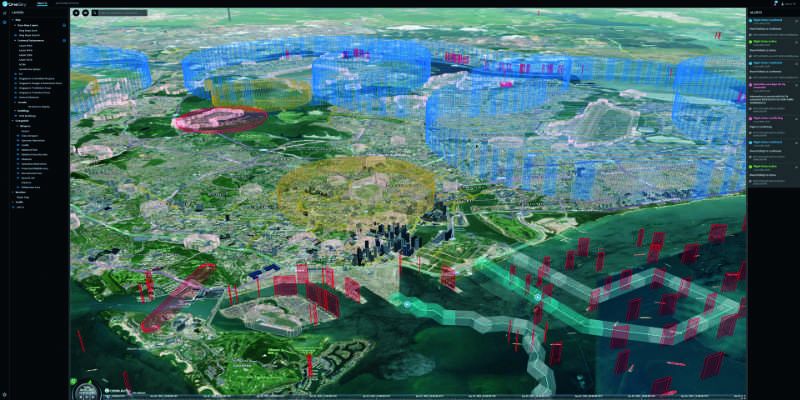

Hence the development of Unmanned Aircraft System Traffic Management (UTM) systems to deconflict airspace shared by many drones and potentially, manned aviation. Skyports’ UTM partner is OneSky. The company’s dynamic UTM system grew out of the same technology used to prevent collisions between commercial satellites.

“We help the ANSPs [Air Navigation Service Providers] responsible for crewed aviation understand the framework needed to control drones in their airspace,” explains OneSky’s head of strategic partnerships, Chris Kucera.

“Our UTM system passes ANSP data to drone operators. It can represent the operator’s flight plan and get it authorized by the ANSP. It is essentially a broker of data between the drone and air traffic management.”

OneSky’s UTM system integrates manned and unmanned aviation by providing an interface between drones and air navigation service providers that enables the latter to manage drone traffic. Meanwhile, OneSky’s Operations Centre provides an interface for drone operators to plug into the system. Strategic deconfliction between multiple operators is achieved solely by the sharing of flight plans over the internet.

“Drones come into a world built for larger aircraft and devoid of infrastructure supporting low altitude flight,” says Kucera. “NASA invented UTM to avoid building infrastructure everywhere. People who want to fly safely should communicate their intent. If everything in the sky is networked, we can do strategic deconfliction by sharing that information. In time, that may evolve into tactical deconfliction based on real-time tracking.”

UTM & U-SPACE development

OneSky first flight-tested its system in Australia, then in Singapore for three years. In the USA, it participated in four NASA pilot programs and further FAA trials to mature the technology. NASA’s advanced tests involved upwards of two dozen drones flying simultaneously, though some of the drones are more real than others.

“Early tests had just one or two live vehicles,” says Kucera. “Later, we had eight UTM companies each controlling their own drones and doing strategic deconfliction.

“But flying drones is costly, so tests usually involve both live and simulated vehicles. After ten years, our mature systems for strategic deconfliction have been proven in operations.”

The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) defines U-Space as a set of digital and automated services to enable safe integration of drones and manned aviation in a volume of airspace. In October 2022, the Port of Rotterdam Authority (PoR) assumed control of its airspace from LNVL, the Dutch ANSP, for a two-year U-Space prototype project using the Airwayz Dynamic UTM system.

“Rotterdam is the largest seaport in the Western world,” says Airwayz CEO, Eyal Zor. “They already have twenty drone operators doing search and rescue, inspection, asset monitoring and policing.

“Previously, the approach was segregation and hoping for the best. The project aims to improve safety and enable more activity.”

Integration into the Airwayz UTM requires each operator to adopt a software layer called the drone operating system (UAVOS) to manage multiple drones. The UAVOS submits flight plans to the UTM for checking and approval. The UTM also monitors in real time to prevent any potential crashes.

“We do not believe in static corridors or segregation, because you quickly run out of airspace,” says Tomer Sorek, business manager at Airwayz. “Dynamic airspace is complex and requires constant monitoring. The UAVOS communicates with our server and we connect to the PoR Robin radar system.

“If something changes, we recalculate everything in proximity and if necessary reroute one of the parties. It is like a control tower talking to pilots, but with systems talking to each other.”

Shipping opportunities

Airwayz is working with LVNL and the Dutch Aerospace Centre (NLR) on UTM-ATM integration. In Rotterdam, drones may avoid collisions with helicopters flying at low altitude by dynamic airspace reconfiguration. When a helicopter communicates its intended flight path, the UTM system will temporarily close that section of airspace to drones until the helicopter has passed.

Planned integration with Harbormaster systems will help the UTM understand the position and movement of ships, not merely as obstacles but as targets for inspection or landing. Airwayz aspires to extend its drone services to anchored ships in the English Channel.

The company’s founders learned about ATM in the Israeli Air Force and matured their civilian technology through the state-funded Israel National Drone Initiative. “In military operations, the infantry, air force, navy and artillery will all fly drones,” says Sorek.

“Airwayz developed an automated system as the only way to avoid near-misses. Israel gave us a great structure to go from early-days UAVOS to thousands of commercial flights with tactical deconfliction. We have already done 20,000 beyond-visual-line-of-sight flights, far more than many competitors.”

EASA defines four levels of U-Space services with increasing levels of complexity. Co-ordinated by ATM services provider EUROCONTROL, the U-ELCOME project aims to implement U1 and U2 services including registration, identification, flight planning, approval and tracking and interfacing with conventional ATM. The program’s three clusters aim to establish commercial drone operations in France, Spain and Italy. In June 2023, U-ELCOME opened a BVLOS corridor in Brétigny-sur-Orge and livestreamed the first flight at the Paris Airshow.

“A mission request for the inaugural flight was submitted to the airspace manager using the Thales ScaleFlyt platform,” EUROCONTROL says. “This was received and approved by the airspace manager, Systematic, using the Thales TopSky system. The drone was equipped with a Thales ScaleFlyt Remote ID tracker developed for real-time BVLOS flight monitoring.”

Launched in November 2022, U-ELCOME will run for three years. Researchers are taking an iterative approach in local ecosystems and the amount of flight testing is planned to increase significantly in 2024. In Spain, U-ELCOME has seen flights associated with firefighting, police and harbor applications while in Italy, a flight campaign to include antenna inspections is underway. U-ELCOME’s end goal is to enable routine drone operations across Europe by 2026.

Meanwhile in the UK, Project Skyway aims to establish a 165 mile (265km) BVLOS drone corridor. It is led by Altitude Angel, whose UTM platform will handle flight approval and deconfliction in conjunction with ground-based sensors to detect and identify drones. UK telecoms provider BT previously led Project XCelerate, which developed a 5 mile (8km) corridor and will explore how its telecoms infrastructure could be leveraged to support U-Space operations as part of Skyway.

“Our masts and structures could carry detection devices looking at the sky to provide situational awareness,” says BT’s drone director, Dave Pankhurst. “That information could then be communicated over our network then ingested and fused with known information by Altitude Angel’s platform.

“If something has changed, they begin deconflicting flight plans. Our existing mobile network can provide communications to the drones themselves for command and control and returning video imagery.”

(Photo: BT)

EUROCONTROL believes BVLOS flights could be tracked using drone-mounted devices or through software integration between UTM platforms and drone control stations. But at the Brétigny-sur-Orge test site it anticipates deployment of ground-based surveillance infrastructure, which has the advantage of detecting non-collaborative vehicles. This could be achieved by radar or so-called sniffers which detect radio frequency signals from drones.

Analogous architecture

If the free market FAA and EASA approaches to UTM seem complex consider Singapore, where the government may simply purchase and run a centralized UTM system. But free markets still require federated architectures whereby drone operators can choose between UTM systems working concurrently in one airspace. EASA defines a Common Information System (CIS) layer to enable deconfliction between UTMs in a federated world.

“The CIS sits underneath a federated model and tells each UTM what the others are doing,” Pankhurst says. “It could be a platform for sharing data, or share responsibility with ground-based detection infrastructure. Either way, BT is well-placed to help move that forward.”

In the UK, BVLOS flights are only permitted for three-month periods in segregated temporary danger areas (TDAs). Skyports is working with the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) to transition TDAs to a temporary reserved areas (TRAs) shared by drones and other aircraft, then transponder mandatory zones (TMZ) where any suitably-equipped aircraft may fly. Project Skyway likewise aims to reduce BVLOS entry barriers.

“Once we prove one level of safety, the CAA may consider the depth of detect-and-avoid technology required for given locations,” says Pankhurst. “Eventually, operators could obtain approval because they are using a UTM system proven to be safe, rather than gathering years of safety evidence and building their own ground-based detect-and-avoid systems.”

EUROCONTROL notes there is a need for early partnerships with national authorities approving BVLOS corridors for the first time. Sorek sees often underfunded regulators trying to chase a fast-evolving drone market. This results in roadblocks, wherein Pankhurst applauds the bravery of companies like Altitude Angel which are willing to invest and move forward. Kucera believes governments should lead by investing in software infrastructure.

“Essentially, that means aligning a system to the ANSP’s flight approval process,” Kucera says. “A drone using UTM solves one side of the problem. But it is hard to fly drones unless we also know where manned aircraft are. That may require conspicuity mandates for aircraft flying below 400ft to report their position. Not all aviators want that, but it’s the only way to ensure safety.

“Everything is based on assumptions. It is about how we make small steps until eventually, we get there,” Kucera says.

Drone delivers Fish and Chips in Orkney

Skyports has operated three BVLOS projects for the UK’s National Health Service. It has collected Covid-19 test samples in Scotland, conducted 14,000 flights collecting lab samples from Scottish hospitals and most recently, transported pathology samples in Newcastle.

“We’ve trended towards more complex missions,” says Skyports’ head of technology, Jef Geudens. “In Newcastle, we flew up to 80km with dangerous goods approval. It could mean cancer patients can receive chemotherapy at home.”

Skyports is also delivering Royal Mail parcels for the Orkney I-Ports project. Royal Mail sorts the parcels into boxes which are flown from Aberdeen to Kirkwall, where Skyports puts them on drones for

onward delivery.

“We can deliver parcels with a 90% availability rate,” says Geudens. “Every Friday, we deliver fish and chips on the islands. We started delivering 2kg and now deliver 20kg each week. Virtually everyone there is eating our fish and chips.”

The Orkney drones operate under BVLOS with visual mitigation (BVLOS-VM) conditions. “We daisy-chain people on each island to maintain visual contact and see that no one else infringes the airspace,” Geudens explains. “BVLOS-VM requires filing an operational safety case, but no operational change.”