Later this year, the Sierra Space Dream Chaser spaceplane is expected to launch into orbit for the first time atop a United Launch Alliance Vulcan Centaur rocket, loaded with cargo bound for the International Space Station. Once in space, it will separate from its fairing and catch up with the ISS as both vehicles hurtle around Earth at 17,000mph (273,000km/h).

“The International Space Station [ISS] pulls us in with its arm,” explains Sierra Space senior vice president of safety and mission assurance, Angie Wise. “We remain docked for up to 75 days while the crew unloads our Shooting Star cargo module and reloads it with trash. We then push away, re-enter Earth’s atmosphere and autonomously land on a runway, while Shooting Star separates and burns up on re-entry.”

In generating the immense kinetic energy required to escape Earth’s gravity, the Vulcan Centaur will expose Dream Chaser and Shooting Star to punishing levels of vibration and sound. Comprehensive vibroacoustic testing at facilities including at the NASA Armstrong Test Facility (ATF) in Sandusky, Ohio aims to ensure their survival.

“We have predictions of the environment the payload will see on the launch vehicle,” says Luke Staab, who was ATF test manager for the Dream Chaser tests. “Because Dream Chaser will dock with the ISS – which has humans aboard – our safety standards increase. We want to find any problems on Earth, so we don’t have to fix them in space.”

Early to modal tests

Structural and vibration tests expose a vehicle to forces expected during launch and measure its responses. These responses are already well-understood in computer models, which physical tests serve to validate. Early-build modal tests induce vibrations into structures and use accelerometers to capture natural resonances and mode shapes, which are crucial in tuning virtual models to physical spacecraft.

Dream Chaser underwent static load tests at the Sierra Space Dream Factory in Louisville, Colorado. “We did those before integrating major subsystems in case we had to modify the primary structure,” says Sierra Space’s vice president of integration and test, Klint Combs. “We mounted the vehicle on a load frame, attached more than 700 strain gauges, applied loads across the structure, and verified the results against our model.”

Pyrotechnic release mechanisms will enable Dream Chaser to separate from its launch vehicle and the Shooting Star before re-entry. Shock event tests conducted jointly with rocket provider United Launch Alliance (ULA) demonstrated these mechanisms and the vehicles’ abilities to withstand the shocks they induce.

“We also tested release mechanisms for the solar arrays, which are folded inside the fairing and then released in orbit,” says Combs. “We fired those release mechanisms, in particular to verify that none of the avionics are affected.”

Mechanical testing

Dream Chaser’s next stop was the Vibroacoustic High Bay at ATF, home to the world’s largest vibration table. Originally built to accommodate testing of the Orion spacecraft, the donut-shaped table required a special cover to accommodate Dream Chaser and Shooting Star upright in launch configuration for mechanical vibration tests in the 2Hz to 100Hz range.

“The system is powered by hydraulic actuators allowing us to test in different directions without changing the test article’s configuration,” says Staab.

“We tested to a qualification level which includes some margin, capturing data from thousands of channels of instrumentation.”

Spaced across six weeks, individual tests took less than five minutes, but required months of preparation. NASA honed its control of the table at the required frequencies using a pathfinder test article to replicate Dream Chaser’s mass. “On the vibration table, we test like we fly,” says Combs. “We put the spaceplane and module together in launch mode with all systems powered on. We exposed them to lower frequencies mechanically induced by the rocket, demonstrating it will survive that part of the launch.”

Before the vibration tests, NASA implemented a modal fixed-base correction method developed by ATA Engineering. A novel proxy for modal testing, the method isolates a test article’s fundamental frequencies by analysis to eliminate the vibration table’s movements. It was performed on a space-bound test article for the first time.

Vibration tables recreate mechanically coupled, low-frequency energy transferred from rocket to spacecraft via bolted joints, while acoustic tests involve higher-frequency, decoupled pressure waves traveling through the air. Vibration most affects massy components, whereas sound excites thinner parts like panels and lenses.

“Vibration tests stop at 100Hz, whereas acoustic tests go up to 10kHz,” says Acoustic Research Systems (ARS) director of applications, Dale Schick.

“They test workmanship at lower and higher frequencies. If you compare pre- and post-low-level tests and all the frequencies align, your test article is well-constructed.”

Acoustic testing

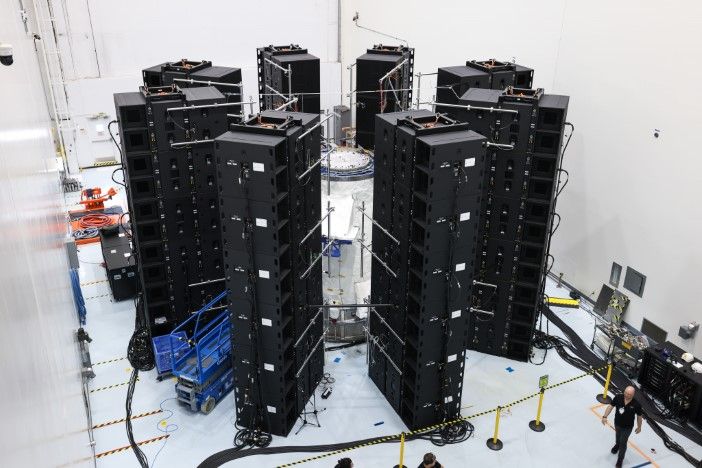

In September 2024, Shooting Star underwent direct field acoustic testing (DFAT or DFAN) in the Space Systems Processing Facility (SSPF) at NASA Kennedy Space Center, Florida. 48

ARS-developed Neutron acoustic devices positioned in stacks of six blasted the module with sound up to a proto-flight qualification level in excess of 140dB. Individual microphones were used to validate and control the field of each acoustic device.

“Our Neutrons are building blocks, like Lego,” says Schick. “We load them in, attach microphone support structures, stack them up, connect the stacks to amplifiers and perform a bare chamber run to demonstrate capability to the customer. We then wheel in their device and connect accelerometers to do the validation.”

Performed at SSPF for the first time, DFAN has emerged as an alternative to reverberant field tests. These are conducted in acoustic chambers where sound produced by pumping compressed nitrogen through electro-pneumatic horns bounces around, becomes diffuse and recreates the launch environment.

“Reverberant tests are notoriously hard to control,” says Schick. “The chambers are expensive and create nitrogen-rich environments where anyone walking in would asphyxiate. Because they’re not portable, you have to ship your bird to the chamber, but we come to you and build the test around your spacecraft.”

Following the Shooting Star test, ARS will perform DFAN tests on Dream Chaser itself. Whereas the Shooting Star test deployed 48 Neutron speakers in stacks of six, the Dream Chaser test requires 90 Neutrons in stacks of ten to match the vehicle’s height with a direct field where sound is the most evenly distributed.

Hundreds of accelerometers will measure the local acceleration response of each panel, part and instrument, each producing a specific signature whose peaks and troughs of frequency and amplitude should match Sierra’s mechanical analysis. The key outcome is model validation and prior modeling makes failure comparatively unlikely.

“Failure could take two forms,” says Schick. “One is a telemetry or electrical failure, if you excite some oscillator in a component. But more likely is a workmanship failure, because something wasn’t torqued correctly or needs more fasteners. That simply means you understand your part better now, so you redesign it and retest.”

Angie Wise leads a Sierra Space workmanship team that closely shadows technicians, performing inspections after assembly and where an issue identified in testing has been fixed. When an asset like Dream Chaser completes a test without revealing any workmanship issues, there are plenty of high-fives.

“During testing, we don’t want eventful days,” says Wise. “Sometimes we find abnormal responses and that’s fine. That’s why we test on the ground – so we don’t have issues on orbit.”

Re-entry testing

The Dream Chaser Tenacity cargo spacecraft will launch inside a fairing, but a crewed variant may sit unsheathed atop a rocket. Launch and ascent is a key mission phase for any spacecraft, but cannot be wholly simulated. Responses to loads, sound waves and vibration are tested separately and wedded in models.

“Coupled load and acoustic analyses predict low-frequency and high-frequency environments, which we assume will combine linearly,” explains Staab. “If available, previous flight data is used to define test environments. Acquisition systems and instrumentation continually improve. We inch closer to realism, adding a margin to reflect uncertainty.”

On re-entry, Dream Chaser will hit the Earth’s atmosphere at Mach 25 and create friction-induced temperatures around 2,500°F (1,370°C), before slowing and landing autonomously on a runway. Its primary structure and landing gear will be tested under loads associated with touchdown, braking and crosswinds, while flight-testing saw a Dream Chaser test article dropped from a helicopter at 10,000ft.

“We demonstrated the vehicle shape working as expected,” says Wise. “Second test, we added maneuvers taking it off-course. Our guidance, navigation and control algorithms adjusted and brought it back to the runway.”

The energy demands of heating a full-size spacecraft to 2500°F (1,370°C) make recreating the hot phase of re-entry impossible on Earth. Dream Chaser’s thermal protection system combines silica-based tiles for the belly and heatshield with TUFROC composite covering the nose and leading edges. Whole-system performance is extrapolated from subsystem component tests.

“Arcjet testing can expose individual tile designs to re-entry temperatures and test how small assemblies of tiles perform together,” says Combs. “We can also demonstrate a history of multiple vehicles using similar technology with a good survival rate.”

Combs and Wise have devoted much of their careers to a spacecraft finally poised for its maiden launch. The company ethos encourages employees to enjoy the journey, while ground tests can assuage many uncertainties. Yet anxiety persists. “They pay me to worry about the mission,” says Wise. “Our team assesses the possible failures and ensures we do all the testing needed before flight. When the vehicle stops on the runway, that’s when you’ll see me relax.”

Dream Chaser opens up orbital possibilities

The Sierra Space Dream Chaser is a reusable spaceplane based on the NASA HL-20 lifting body concept. Originally conceived as a crewed vehicle, Sierra pivoted to a cargo variant for NASA’s Commercial Resupply Services Contract. Dream Chaser Tenacity will rendezvous with the International Space Station (ISS) later this year, its non-reusable Shooting Star module laden with cargo.

“Since the Space Shuttle retired, there’s been a need for a versatile, reusable spacecraft to support missions in low-Earth orbit, including cargo resupply and crewed transport to ISS and future orbital platforms,” says Sierra Space’s vice president of integration and test, Klint Combs. “Our vehicle can also be an independent orbital science platform.”

Like the Space Shuttle, Dream Chaser is reusable, lands on a runway and provides a low-g re-entry environment favorable to microgravity experiments. Designed to provide affordable space access and unlock a LEO economy, it is smaller and lighter than the Shuttle.

“The Dream Chaser’s compact size allows us to launch on pre-existing rockets, so we don’t have to develop them,” says Combs. “Whereas the Space Shuttle was a delta wing design, we’re a lifting body, making us more efficient on re-entry and better for whole-vehicle heat dissipation.”

Plans for a crewed variant require just a few modifications. Tenacity will launch with wings folded inside a fairing, but a crewed variant would launch unfaired to accommodate an emergency abort system.

“We will be able to separate if there’s a bad day on the rocket,” says Sierra Space senior vice president of safety and mission assurance Angie Wise. “For re-entry, we’ll add some dissimilar redundancy and consider how much controllability we give the crew.”

Tenacity already complies with many of NASA’s rigorous safety standards for human-rated vehicles.

“We have to keep cargo pressurized and be able to fly live animals,” says Wise. “We mate with the ISS and have astronauts going in and out unloading cargo, so life support is already incorporated.”

A sound testing approach

The patented design of the Acoustic Research Systems Neutron acoustic devices used in direct field acoustic (DFAN) tests enables them to produce rocket launch levels of sound from the power of a single wall outlet.

“Other systems use at least three times more power and risk burning drivers more often,” says Acoustic Research Systems (ARS) director of applications, Dale Schick. “We put lots of drivers into one Neutron and configure them to be super-efficient. Each Neutron produces the same broadband energy from 20Hz to 10kHz. We’ve never blown one driver, even for 151dB tests.”

Founded after demand for live sound rental equipment disappeared during Covid, ARS has rapidly grown its peripatetic DFAN business. While Shooting Star is the largest payload tested by DFAN to date, the forthcoming Dream Chaser test will be almost double the size. Large-scale DFAN tests create a certain rock-star cachet.

“Like the launch, it’s a test people don’t want to miss,” says Schick. “The company CEO always turns up. People think it’s the coolest thing ever – almost like they want an autograph.”

Now, ARS hopes to use sound as the forcing function in the modal tests crucial to creating lifelike computer models. Currently, costly, expert-led modal testing excites structures with hammers or shakers.

“We think acoustic energy can excite the same modes,” says Schick. “We’re figuring out how to excite low frequencies and move 3000 lbs structures to 2Hz with sound. I don’t know if that’s been done before.”