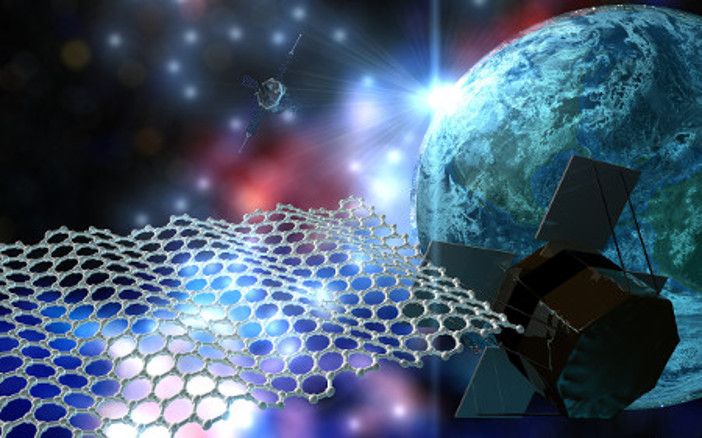

The European Space Agency and the EU-research group the Graphene Flagship have successfully shown the potential for graphene in space applications with a series of tests.

Graphene’s excellent thermal properties offer opportunities to improve the performance of loop heat pipes, thermal management systems used in aerospace and satellite applications.

Graphene could also have a use in space propulsion, due to its lightness and strong interaction with light.

Researchers from the Graphene Flagship, a €1bn (US$1.2bn), 10-year EU research initiative formed of 150 academic and industrial research groups from 23 countries, tested both of these applications in experiments during November and December 2017.

Professor Andrea Ferrari, science and technology officer of the Graphene Flagship, from the University of Cambridge, UK, said, “Graphene as we know has a lot of opportunities. One of them, recognized early on, is space applications, and this is the first time that graphene has been tested in space-like applications, worldwide.”

Graphene is a single layer of carbon atoms, arranged in a hexagonal lattice. It is an extremely thin, flexible, strong and light material, and is also impermeable to molecules and very electrically and thermally conductive.

Loop heat pipe tests

The thermal pipe experiment

The main element of the loop heat pipe is the metallic wick, where heat is transferred from a hot object into a fluid, which cools the system. Two different types of graphene were tested during experiments last year.

Dr Marco Molina, chief technical officer at Leonardo’s space business, said, “We are aiming to increase the lifetime and improve the autonomy of satellites and space probes. By adding graphene, we will have a more reliable loop heat pipe, capable to operate autonomously in space.”

After successful laboratory tests, the wicks for the loop heat pipes were tested in two ESA parabolic flight campaigns during November and December. “We have good tests done on Earth in the lab. But because the applications will be in satellites, we needed to see how the wicks perform in low-gravity conditions and also in hypergravity conditions, to simulate a satellite launch,” said Ferrari.

The results of the parabolic flight confirmed the improvements to the wick, and engineers at the Flagship are now developing the graphene-based heat pipes toward a commercial product.

Vincenzo Palermo, vice-director of the Graphene Flagship, said, “We have tested the principle and the core of the device. The next step will be to optimize the whole device, and have a full heat pipe that can go in a satellite.”

Propulsion preparations

The aircraft used for the parabolic flight

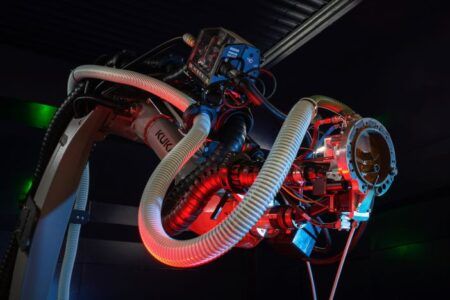

Researchers from Delft Technical University, the Netherlands, tested the potential of graphene to be used in space-propulsion with an experiment in microgravity at the ZARM Drop Tower in Bremen, Germany.

To create extreme microgravity conditions, down to one millionth of the Earth’s gravitational force, a capsule containing the experiment was catapulted up and down the 146m tower, leading to 9.3 seconds of weightlessness. The TU Delft Space Institute, the Netherlands, also supported the GrapheneX project.

The GrapheneX team designed and built the experiment to test graphene for use in solar sails using free-floating graphene membranes provided by firm Graphenea.

Solar sails can be used in space as a method of propelling spacecraft using light from the sun or from Earth-based lasers. When light is reflected from or absorbed by a surface, it exerts a force that pushes the surface away from the light source. This radiation pressure can be used to propel objects in space without using fuel or gases.

The aim of the research was to test how the graphene membranes would behave under radiation pressure from lasers. The experiment ran five times over November 13-17, 2017.

Rocco Gaudenzi, a researcher on the GrapheneX team, said, “Our experiment was like complex clockwork where every component has to go off seamlessly at the right time. It does not often happen that you have to build up such a clockwork from scratch, and you cannot test it in real conditions but during the launch itself.”

Final setup of the solar sail experiment

Davide Stefani, a GrapheneX researcher, said, “Despite initial technical difficulties, we managed to quickly figure out what was going on, fix the issues and get back on track. We are very happy with the results of the experiment as we observed laser-induced motion of a graphene light sail.”

The researchers are now considering further tests as part of a project to continue exploring the influence of radiation pressure on graphene light sails.

Janauary 17, 2018

This article was originally published on the Graphene Flagship website here.