Complex and technically advanced non destructive testing technologies are increasingly being used on operational aircraft, with suppliers and users facing challenges as devices move from the laboratory to the hangar.

Waygate Technologies, which is a Baker Hughes business makes NDT equipment for remote visual inspection (RVI), ultrasonic testing (UT), and industrial x-ray computed tomography (CT). These inspection technologies are used to test initial materials as well as finished aircraft components and are also being used as part of in-field maintenance processes.

The company’s Real3D technology displays components as a 3D model and includes various software tools to measure internal and external features and detect various kinds of defects.

According to Henning Juknat from Waygate, as the use of composites in aerospace has increased, so has the industry’s reliance on UT. However, the technology used for composite part inspection will vary.

“Different technologies have different strengths, depending on the material and geometry of the part being inspected and the surrounding parts in assemblies,” says Juknat. “For example, industrial CT systems can be best used to inspect individual turbine blades, while the same blade as part of an engine on a wing might be better suited to RVI borescope or ultrasonic inspection.”

The aerospace industry is conservative with innovation, relying on “well-proven” technologies for inspection, but always wants to improve productivity and extend the lifetime of components. “It takes time to trial, test and validate new technologies, but we have developed close relationships with our end users to ensure that we have an understanding of the challenges and opportunities so that we can continue to invest in the right areas,” says Juknat.

Approved technology

Matt Day, UK and Ireland sales manager for NDT equipment provider Dolphitech agrees there can be a lag between ambition and reality: “OEMs can take years to approve new technology unless there is a problem that needs a solution quickly. If the process of sourcing new technologies is well documented with an obvious solution to a clear problem, then they can move extremely quickly.”

The company’s Dolphicam2 products are used to measure composites, metals and multi-layered materials. In May 2014, DolphiCam was accepted for NDT on the Boeing 787 Dreamliner. Dolphitech also worked with Airbus on the certification of the technology for the A350 XWB for impact damage assessment of its carbon fiber reinforced plastic skin.

According to Day, composites present a challenge for NDT because, unlike metals, barely visible impact damage is difficult to identify. “A small mark on the surface can result in a problem 30-40mm in diameter underneath,” Day says.

The main focus is the speed at which people want to find defects, and the ability to use the data as quickly as possible. As well as this, “more companies are pushing towards the digital arena and everybody’s talking about NDT 4.0,” he says.

Scalability

Adaptix has developed a form of industrial 3D x-ray technology that uses digital tomosynthesis (DT) rather than CT. “We are not saying this technique will replace ultrasound or CT in aerospace inspection, but it can add a new tool to aerospace to drastically reduce reliance on both,” says Andy Barnes, managing director, NDE at the company.

Recently, Adaptix participated in a UK Government funded program to develop AI-based auto-defect detection technology. According to Barnes, Adaptix has the only deployable large 3D x-ray unit in the world that can image the trailing edge of an Airbus wing and other parts in situ.

“We are currently scaling this to robot mount the capability for manufacture and through life,” Barnes says. “With no other method scalable to inspect a full wing with 3D x-ray, we are in a great position to enable auto-inspection, NDE4.0 and digital twins to aerospace for even the largest parts.”

Barnes believes that while aerospace has proactive individuals and business units for R&D, startups can find the slow pace of technology implementation in aerospace tough. Another challenge with using NDT in maintenance is the lack of skills, as well as the cost of qualification. AI could help solve this problem.

“While defects need to be registered by a qualified human inspector, we can reduce the burden on the workforce by introducing AI software to help automate the process,” says Barnes.

“Eventually, we are aiming to have an automated robotic detection system to inspect parts on manufacture, register the digital twin with a quality assurance plan, then inspect the through life according to that plan using the same robotic auto-detection system with accompanying software. If we do this, we will have realized NDE4.0.”

Real-time plotting

UK-based R&D service and training provider TWI’s IntACom program aims to reduce the cost of inspecting components with complex geometries in the aerospace industry.

One of the projects delivered a prototype automated inspection cell using two six-axis robot arms that can inspect highly curved components in less time than existing systems. The program reached technology readiness level (TRL) 9 and is now routinely used as part of an inspection service for aerospace manufacturers who send volume parts to TWI.

In the cell, data is collected from both an ultrasonic data acquisition unit and either one or two robots simultaneously. This allows for real-time 3D plotting and display of the data against a CAD model, making locating a defect within the component quick and easy, which helps improve safety.

Dr Calum Hoyle, software and robot team manager at TWI says, “The ability to map in 3D the UT data based on a robotic feed allows greater defect measurement accuracy to be achieved when compared to a human operator. This is primarily down to the large size of the component which makes achieving continuity with a human inspector difficult.”

Composites offer special challenges to NDT technology. Ian Nicholson, consultant engineer at TWI says, “Higher attenuation, and varying velocity profiles due to different layer makeups make post-processing data more challenging.

“Users tend to rely more on lower frequency probes to increase penetration through the material. However, this increases wavelength and therefore reduces the resolution for the total focusing method and minimum detectable defect size.”

Automation and robotics

To most equipment suppliers, robotics and automation are fast becoming a part of the offering to users in the aerospace sector. According to Juknat, AI and assisted / automated defect recognition (ADR) are a rapidly evolving aspect of NDT.

“We passionately believe that AI and robotics have a real opportunity to deliver productivity gains as part of in-situ inspection workflows,” Juknat says. “Others in the industry feel the same. There are numerous publicly available examples of such technologies being developed to deliver productivity gains.”

Day agrees that increased productivity is a big plus for AI: “Machine learning is becoming more prevalent, especially for high volume production and in the manufacture of 3D printed parts,”

“There are only a few companies that can carry out CT inspection as a service and it can be very expensive. Machine learning can reduce the number of parts that need to go through a CT inspection by up to 30 times, and achieve the same level of confidence.”

However, most people agree that machine learning and AI will not replace the human in the loop human for final sign-off or for second opinions. The human will always be there.

Morgan Ward NDT carries out inspections on aircraft around the world and works with suppliers within the UK at their production sites. The company also inspects parts in-house.

According to Ben Kirkpatrick, technical director, advances in technology within the sector mean that probes and equipment have better screen resolutions and more storage capacity for data.

“It helps technicians find smaller defects at an earlier stage, which helps to prevent an aircraft having a maintenance or a safety issue,” says Kirkpatrick.

“Automation and robotics are already used in the manufacturing process on a large scale, but an NDT inspector will always be required as there are always be anomalies.”

Moreover, Kirkpatrick believes that variables in operational aircraft such as previous repairs, access to different hangar configurations or the availability of the machines to carry out the inspections will make the implementation of AI more difficult.

Nicholson feels that AI and machine learning have applications in automated defect recognition and for analyzing large amounts of data but warns that more development needs to be undertaken. “We need to be sure it won’t miss any defects or miss or false call ones,” he asks.

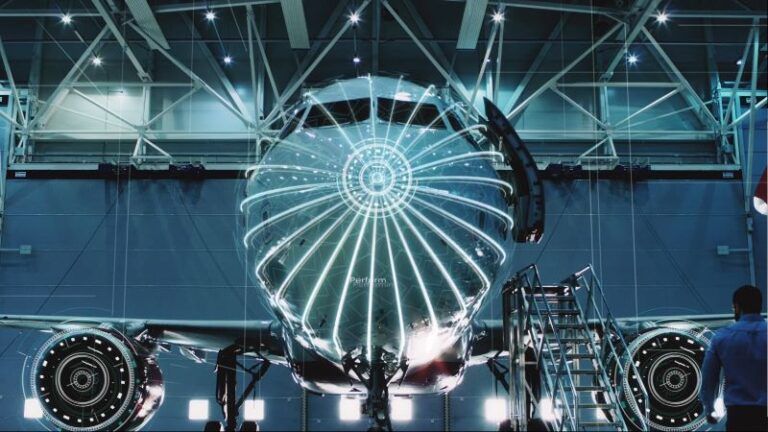

“The ultimate vision is the deployment of inspection systems using robotic arms mounted on mobile platforms deploying NDT inspection techniques,” Nicholson says. “Upon routine arrival of the plane into the hangar, these mobile robots would exit from their dock charging stations and know what areas of the plane to inspect, collect the inspection data required, and generate an NDT report to confirm if the inspected parts on the plane are still fit for purpose.”

Changes in the industry will dictate the development of NDT technology believes Day: “More companies are using composites, not just Airbus and Boeing. There are new eVTOL aircraft and drone manufacturers,” he says. “These aircraft must be inspected, and we do see cases where we cannot penetrate the material with ultrasound.

“Companies have the technology to bond two materials together, but because of the number of variables – plies, resin, temperature, vacuum, the final project material can be altered very easily, making it hard to build up a database of reference standards.”

However, Day is optimistic about new ways of working prompted by the Covid lockdown, such as the concept of remote witnessing of inspections a process the FAA set out the criteria for during the Covid-19 pandemic. He says, “We can inspect things in person and a working procedure for witnessing remotely has been agreed. This means a Level 3 inspector can stay in their office and monitor multiple inspectors from a central location without having to travel.”