The Cirrus SF50 Vision personal jet is nearing completion of the type certification process that began in 2008, but the FAA has no plans to evaluate the whole aircraft ballistic parachute recovery system, which would involve potentially dangerous (and expensive) flight testing. The technology – the Cirrus Airframe Parachute System (CAPS) – is designed to safely bring the aircraft intact down to earth in an emergency. A parachute system installed on other Cirrus aircraft is credited by the company with saving about 100 lives.

The FAA detailed in a Notice of Proposed Special Conditions how it intends to approve the SF50’s parachute system: “Potential emergencies include, but are not limited to: loss of power or thrust; loss of airplane control; pilot disorientation; pilot incapacitation with a passenger on board; mechanical or structural failure; icing; and accidents resulting from pilot negligence or error. The recovery system should prioritize protection from most probable hazards, but it is not reasonable to expect it to protect occupants from every possible situation.”

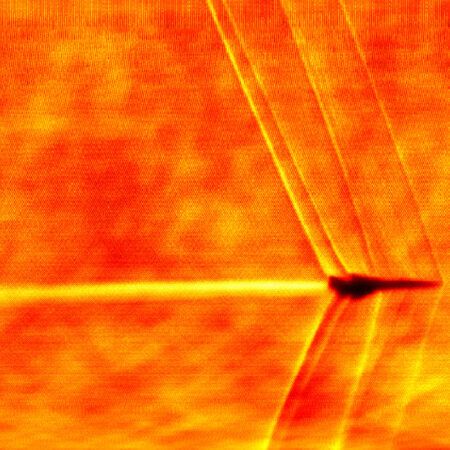

A major design difference between the SF50 CAPS and Cirrus’s previously approved parachute technology is a new component that interfaces with the aircraft’s avionics and flight controls. This is designed to bring the airplane to a “valid deployment envelope speed” of between 67kts and 160kts calibrated airspeed (KCAS) when the parachute system is activated. The CAPS system for the jet also was designed for higher gross weight and maximum activation speed and altitude of operation.

“Since it is a non-required system, the means of substantiation have been altered to reflect the bounds of the operating envelope and the means of analysis that can be substantiated with overlapping lower-level testing/analysis, and to relieve inflight deployment to avoid unnecessary expense and the inherent danger in performing this test,” the notice said.

Systems evaluated as subjects of special conditions must meet two baseline criteria: they must not introduce unacceptable hazards prior to or after activation; and there must be a showing by the applicant that the system does not adversely affect the functioning of other systems, or adversely influence the safety of the aircraft or occupants.

“The applicant does not have to prove or demonstrate that the system works in flight,” the FAA said.

April 1, 2016