NASA engineers are using one of the world’s lightest solid materials in an antenna that could be embedded into the skin of an aircraft, creating a more aerodynamic and reliable communication solution.

The ultra-lightweight aerogel antenna is designed to enable satellite communications where power and space are limited. The aerogel is made up of flexible, high-performance polymers.

The design, 95% of which is made of air offers a combination of low weight and strength. Researchers can adjust its properties to achieve either the flexibility of plastic wrap or the rigidity of plexiglass.

“By removing the liquid portion of a gel, you’re left with this incredibly porous structure,” said Stephanie Vivod, a chemical engineer at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, USA. “If you’ve ever made Jell-O, you’ve performed chemistry that’s similar to the first step of making an aerogel.”

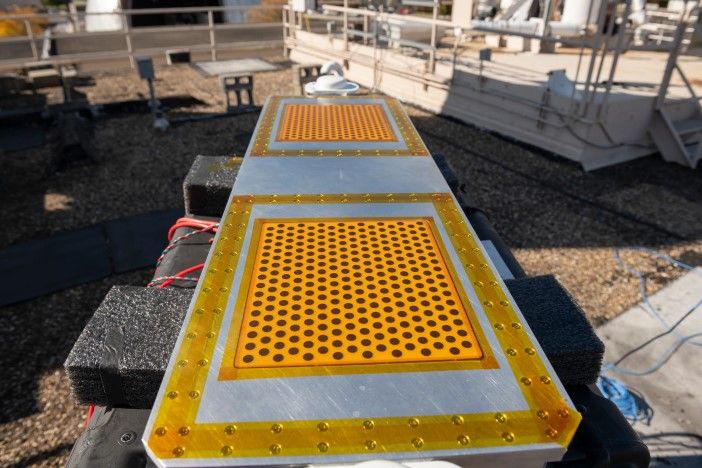

Engineers sandwiched a layer of aerogel between a small circuit board and an array of thin, circular copper cells, then topped the design off with a type of film known for its electrical insulation properties. This innovation is known at NASA and in the aviation community as an active phased array aerogel antenna.

In addition to decreasing drag by conforming to the shape of aircraft, aerogel antennas save weight and space and come with the ability to adjust their individual array elements to reduce signal interference.

The antennas are also less visually intrusive compared to other types of antennas, such as spikes and blades. The finished product looks like a honeycomb but lays flat on an aircraft’s surface.

During summer 2024, researchers flight tested a rigid version of the antenna on a Britten-Norman Defender aircraft with the US Navy at Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Maryland.

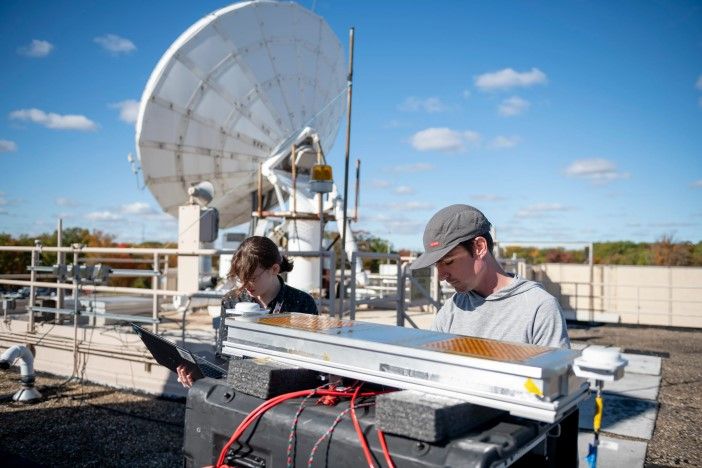

Last October, researchers at NASA Glenn and the satellite communications firm Eutelsat began ground testing a version of the antenna mounted to a platform. The team successfully connected with a Eutelsat satellite in geostationary orbit, which bounced a signal back down to a satellite dish on a building at Glenn.

Other demonstrations of the system at Glenn connected with a constellation of communications satellites operated in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) by the data relay company Kepler. NASA researchers will design, build, and test a flexible version of the antenna later this year.

“This is significant because we are able to use the same antenna to connect with two very different satellite systems,” said Glenn researcher Bryan Schoenholz.

LEO satellites are relatively close – at 1,200 miles from the surface – and move quickly around the planet. Geostationary satellites are much farther – more than 22,000 miles from the surface – but orbit at speeds matching the Earth’s rotation, so they appear to remain in a fixed position above the equator.

Results from the satellite testing have been analyzed to assess the aerogel antenna’s potential usefulness.

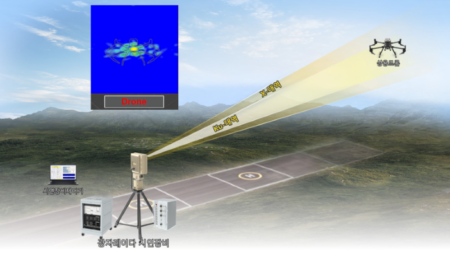

When modern aircraft communicate with stations on the ground, those signals are often transmitted through satellite relays, which can come with delays and loss of communication. This NASA-developed technology can ensure these satellite links are not disrupted during flight as the aerogel antenna’s beam is a concentrated flow of radio waves that can be electronically steered with precision to maintain the connection.

New types of aircraft, including unmanned autonomous BVLOS (Beyond Visual Line of Sight) drones and eVTOL aircraft will be more dependent on communications links than existing aircraft.

“If an autonomous air taxi or drone flight loses its communications link, we have a very unsafe situation,” Schoenholz said. “We can’t afford a dropped call up there because that connection is critical to the safety of the flight.”

Schoenholz, Vivod, and others work on NASA’s Antenna Deployment and Optimization Technologies activity within the Transformational Tools and Technologies project. The activity aims to develop technologies that reduce the risk of radio frequency interference from air taxis, drones, commercial passenger jets, and other aircraft in increasingly crowded airspace.