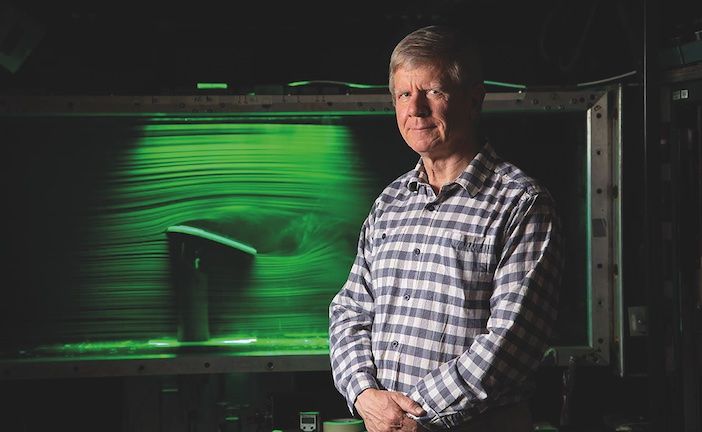

by David Williams, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Illinois Institute of Technology

During the last five years there has been a lot of work done in industry, academia, and by governments looking at how active flow control can be used to improve the flight performance of air vehicles.

Research into active flow control (AFC) far pre-dates my involvement in the area. It was first devised and studied more than one hundred years ago during the early days of flight. The concept was employed intermittently throughout the 20th century. For example, during the 1950s and 1960s several US fighter aircraft used steady blowing jets of air to reattach the air flow over flaps to assist landing. By the 1980s, when I first began working in AFC, we had begun to look at how single, unsteady disturbances of air could create significant control effects with much lower power input.

The fundamental shift is that in the past AFC was mainly used to fix aerodynamic problems with aircraft designs, whereas now engineers are learning how to implement the technique from the start of the design process to improve the overall performance of air vehicles. This was one objective of a NATO research group I was recently involved in – to reduce dependency on traditional control effectors.

During that project we explored several AFC approaches and determined that Coanda-effect blowing on the trailing edge and fluidic thrust vectoring were very efficient for flight vehicle control. Physically, the Coanda trailing-edge effector produces a slot jet that wraps around the trailing edge of the wing and creates changes in lift and pitching moment. When applied together with thrust vectoring, the flight simulations showed sufficient yaw and pitch authority to provide control on two different flight vehicles during cruise conditions.

Researchers at Illinois Tech are now working on a 7.5ft (2.3m) jet to validate these concepts with flight testing, using funding from the Office of Naval Research and the Illinois NASA Space Grant. We have developed a new type of bi-directional Coanda trailing edge actuator for pitch and roll control. We aim to fly it for the first time before the end of this year.

Coming from the research group, my perspective is that defense will see the first applications of AFC for flight control, probably within the next five to ten years. Our assessments showed that an AFC-based flight control system will be smaller and lighter than conventional flight control systems. There are also specific benefits for the military, which include reducing the observability of air vehicles while enhancing their survivability and maneuverability.

I believe the first commercial applications for AFC will come soon after, as people realize that the safety and efficiency of aircraft can be significantly improved using this technology. These types of effectors can help reduce fuel consumption, and they work better in stalled conditions. This helps to improve flight stability compared with traditional-style control effectors.

The next task on the horizon is to prove that AFC can be used to improve overall aircraft efficiency and safety. That will require a multidisciplinary approach. There are groups of people working on the flow control effectors themselves and other groups working on the controls. It is the intersection of these two groups where the flight control algorithms are developed and refined. Another area that needs attention is how to integrate the effectors into design simulations to assess their viability. Significant progress is being made in both of these areas. I strongly believe we are only just beginning to see the benefits this technology can bring to aviation.

More Opinion

How hybrid-electric aircraft can help reshape aviation

How hydrogen-powered aircraft can help meet the climate challenge